Development: Awakening to the World Through Touch

Even before birth, touch is the preferred sense for babies to discover their environment. From the fourth week of pregnancy, certain touch receptors are already emerging: it is the first sensory capacity to appear in the fetus, and the foundation on which the child will develop its relationship with the world through the senses. Touch is important for a baby’s physical growth, but also its emotional well-being, cognitive functions, and overall health. So much so that a lack of human contact can cause significant developmental delays.

The COMET* (Mobility: aging, pathology, health) laboratory at the University of Caen-Normandy is studying how the sensory skills of babies and young children are linked to the development of their attention and cognitive performance. By doing so, Nadège Roche-Labarbe and her team hope to discover new avenues for preventing, identifying, and remediating developmental disorders – including those of attention, learning, and the autism spectrum. An immersion in the delicate sensory world of the very young.

The DECODE scientific program links research projects concerning the development of sensory behaviors and the identification of associated disorders. It is based on different specialties working together: psychology and cognitive sciences, neonatology and pediatrics, brain imaging and biomedical engineering. “We are interested in how the neonatal environment influences the development of brain structures and functions, and we are trying to understand how this in turn will impact the quality of cognitive development, through to performance at school age,” explains Roche-Labarbe.

About 40% of preterm infants present developmental disorders during childhood, common factors of which are sensory and attention abnormalities. The aim of the NEOPRENE project is to establish a link between the sense of touch and the development of attention, in order to identify risk markers for atypical development. The differences in brain structure, neural connections, and cognitive abilities observed in infants born prematurely are linked to their tactile abilities – at 35 weeks of pregnancy, then at 2 years of age.

To assess the tactile perception of premature newborns, a vibrating device called a “matrix” is placed on the child’s forearm. An alignment of four modules that vibrate in one direction or the other generates a stroking sensation. If the vibration is regular, the baby expects to receive the next caress. The researchers then study the brain’s electrical activity to determine whether – or not – it perceives a change in direction or tempo in the stimulus. This electrical activity is measured using an electroencephalogram (EEG). Doing so makes it possible to obtain a precise spatial resolution of the neurons’ activity at the moment when the matrix vibrates. Thanks to these data, the team is able to assess the ability of premature infants to become used to a repeated sensation and predict forthcoming stimuli. This essential skill enables them to adapt to their environment.

Antoine Le Boedec, radiology intern, is analyzing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brains of babies. By observing variations in brain volume and in the connections that form between the neurons, he looks for signs that are predictive of future disorders of psychomotor development and behavior.

Children recruited at birth return two years later for behavioral assessment and psychometric testing. Three critical elements are evaluated: sensory perception, attention, and executive functions – that is to say all of the mental processes implemented to manage behaviors, thoughts, and emotions in a new situation.

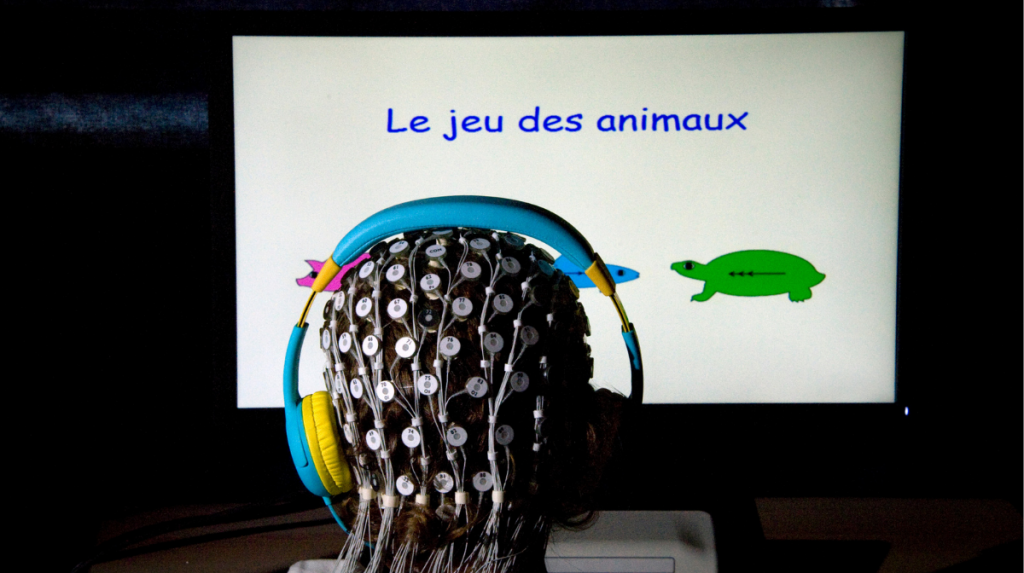

The development of attention in children is assessed using an Attention Network Task (ANT) test. This takes the form of a pared-down video game, in which the child has to decide whether an animal is heading right or left. “Distracting” elements that move in the same or opposite directions appear on the screen; the child must inhibit the distractions and focus on the central animal.

Gross motor skills, important for the coordination of movements and balance, are measured by throwing bags, or jumping on mats. The researchers also assess children’s ability to set a goal and then achieve it by adjusting their behavior.

Sensory capacities are built through movement, which itself depends on the sensory information received. A Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC) makes it possible to estimate their motor control. Fine motor skills, useful for writing, for example, are tested through games in which the child places tokens in a piggy bank, or threads beads.

Between 0 and 2 years of age, the brain is still highly plastic. If sensory difficulties are spotted early enough, interactions with children could be strengthened to compensate for them. In the meantime, the researchers are emphasizing the benefits of the presence of adults and their cuddles – a source of enrichment that medicine can never replace.

Note:

* unit 1075 Inserm/University of Caen-Normandy